We get more of this: “and if memory = pain = being human, I’m not human, I’m a pipe of O telling this story over the course of a single night” “I found Bombay and opium, the drug and the city”. Of course, and as the sentence can’t quite leave unsaid, all this means is simply that “the man and the pipe” are both speaking to us simultaneously, or at least that what we read is the product of their conversation. that I, the I you’re imagining at this moment, a thinking someone who’s writing these words, who’s arranging time in a logical chronological sequence, someone with an overall plan, an engineer-god in the machine, well, that isn’t the I who’s telling this story, that’s the I who’s being told

It makes a lot of this, pretending to something like the form of the smoke exhaled by the first of our ‘I’ narrators – and exhaustively, tortuously, over-complicating the identity of the other.

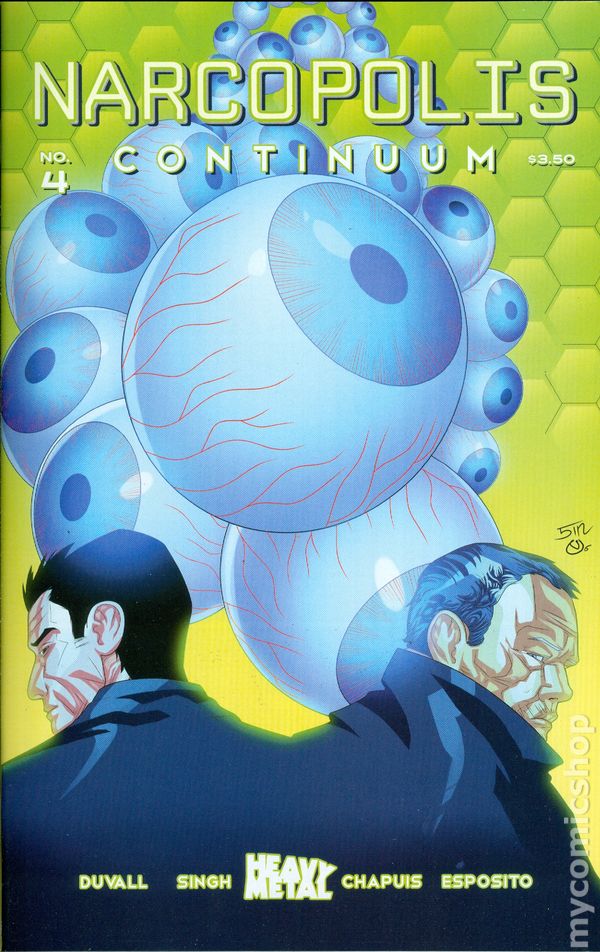

The six-page prologue which begins Jeet Thayil’s debut novel, Narcopolis – a disorienting trawl through India’s recent history seen through the bleary prism of the opium pipe – is a single sentence.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)